Georges Cochon

| L'avancement de cette traduction est de %. |

Le Squat est né à Paris en 1912 avec l'anarchiste moustachu Georges Cochon (1879-1959). Ouvrier tapissier, fondateur de l'Union syndicale des locataires. Il luttait vigoureusement contre les proprios "vautours". La presse et les chansonniers (Charles d'Avray, Montéhus...) popularisaient les actions de ces militants inventeurs du déménagement "à la cloche de bois" qui, alors, se pratiquait en fanfare ! Occupations d'hôtels particuliers, installations de maisons préfabriquées dans les lieux les plus insolites (Tuileries, Chambre des députés, casernes, Préfecture...) avec banderoles, drapeaux et Raffut de Saint-Polycarpe furent le sujet d'un feuilleton publié dans L'Humanité entre le 17 novembre 1935 et le 17 janvier 1936.

Biographie

| Voir l'[ article anglais] par '. |

Georges Alexandre Cochon est né le 26 mars 1879 à Chartres. Gagnant sa vie comme ouvrier en tapisserie, il gravita autour du mouvement anarchiste parisien.

Marrié, il eut trois enfants, deux garçons et une fille. Il servit dans la marine, et prit part à la campagne de Crète. Il passa trois années dans les bataillons punitifs d'Afrique pour objection de conscience. Il fondit un phalanstère communiste à Vanves, qui ne dura que deux mois.

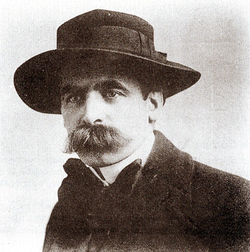

Selon un journaliste du périodique Le Temps, « il parlait de façon très agréable, avec une voix à la fois masculine et tendre, qui devait convaincre plus les femmes que les hommes ». Lorsqu'il avait la trentaine, Cochon portait une large moustache, s'habillait soigneusement et de façon élégante, portant le col blanc et une lavallière. Il portait un grand chapeau noir cerclé d'une bande de rouge, à l'époque où les travailleurs portaient habituellement des casquettes ou des panamas, alors que la bourgeoisie et la police portaient des chapeaux melons. Il portait également un long manteau sur une jaquette sombre.

En février 1911, il devient le secrétaire général de l'Union syndicale des locataires ouvriers et employés, après avoir été son trésorier. Ce n'était que la suite du premier syndicat des locataires créé par l'anarchiste Pennelier en 1903.

Le syndicat des locataires fut fondé à Clichy en 1909, en réponse à la création d'une association de propriétaires, sur l'initiative de la Bourse du Travail et de son secrétaire dynamique, Constant, alias Jean Breton. Ce dernier prit part à la Commune de Paris, fut condamné à la déportation, puis amnistié en 1884. Il fut secrétaire du syndicat des voituriers dans le département de la Seine, affilié à la CGT. Il fut un des plus actifs au sein de la Ligue de la grève des loyers et des loyers fermiers en 1884-1888. Élu secrétaire de la Fédération Nationale des Ouvriers en Voiture en 1911, il rejoint la même année la nouvellement créée Fédération Communiste Anarchiste (FCA). Les objectifs de Constant étaient la baisse initiale des loyers, et la réparation des logements délabrés, l'opposition militante aux expulsions, et à long terme, la grève générale des locataires.

Constant was soon replaced by Marcille, a militant of the Levallois-Perret district, as general secretary. The young anarchist Louis Ragon, secretary of the section of the 5th arrondissement, was his assistant. However, there were already tensions within the union, with the partisans of direct action opposing themselves to those who thought that socialist deputies should be approached for support. Constant accused Marcille of using the union’s money for his own profit. Less than a month after having become general secretary, Marcille had to resign. Cochon then replaced him as general secretary.

Cochon’s activity caused him to be targeted by the landlords and he himself faced eviction in 1911. He refused to leave and endured a siege of five days by the police. He nailed beams across the door and put a lamp in the window of his flat every night of the siege.

The union had its own song, La Marche des Locataires, written by the anarchist Charles d’Avray. The union had 20 sections in June 1911, of which 11 in Paris, and 3,500 members, of which 2,500 were paying members.

The union had concentrated on helping tenants remove all their belongings from their lodgings when they were unable to pay their rent, in operations known as “demenagements a la cloche de boisâ€. Failure to pay back rent often resulted in confiscation of tenants’ belongings by the landlords.

On the announcement of the eviction of a tenant, the union organised a band, Le Raffut de la Sainte Polycarpe, which alerted the neighbourhood and put fear into the concierges and bailiffs. This scratch band had its roots in the charivaris of the Paris of the French Revolution, when women beat on pans to rouse the populace.

When concierges attempted to stop the midnight flits, the union replied by putting bed bugs and cockroaches through their keyholes. Cochon was later to write his 39 Ways of Infuriating Your Concierge.

The moonlight flits were at first secretive and then became public. It was Cochon who pioneered the use of spectacular actions, involving the mass occupation of buildings.

The union had the help of several skilled workers who put together a prefabricated house and trained people to put it together in the quickest time possible. With this prefab they squatted several places like the garden of the Tuileries, the courtyard of the Chamber of Deputies, the Hotel de Ville, where several thousand homeless massed, the barracks of the Chateau d’Eau, where 50 families were moved in, the Madeleine church and even the Prefecture of Police!

The actions of the union were very popular among the working class of Paris. As well as the great anarchist singer-songwriter d’Avray, the union gained the support of another great chansonnier, Montehus, and of Steinlen, the gifted graphic artist and painter who created posters for the cause.

In 1912 he wrote for the Brussels anarchist paper Le Combat Social where he contributed to a regular anti-landlord column, along with Georges Schmickrath and Leon de Wreker. In May 1912 there was a split in the union.

Cochon’s charismatic personality and the singing of his praises in song and on the streets turned him into a celebrity and separated him off from the other militants of the tenants’ union. The spectacular actions, whilst highlighting the housing problem, at the same time turned the media spotlight on Cochon and increased his celebrity.

Coupled with this was the entry of socialists into the union. These two developments meant that the union started moving away from the libertarian principles of its foundation and early development.

Cochon attempted to reconcile the opposing poles of the revolutionaries and the reformists whilst recognising that direct action was the only way to win tenants fights. But he himself was already moving away from his original positions.

A decision to send an open letter to Parliament was taken. It was strongly opposed by anarchists and revolutionary syndicalists who rightly saw this as a move towards pressurising parliament rather than relying on direct action.

In October 1911 Cochon became a full-time worker for the union. Constant resigned from the union in disgust and many sections protested.

Dazzled by his popularity, Cochon announced that he was putting forward his candidacy at the municipal elections of May 1912. He was denounced as a salaud (bastard) in the pages of the anarchist weekly Le Libertaire by other tenants’ activists. The anarchists and revolutionary syndicalists decided to move towards his expulsion from the union, and a month later they were successful.

However, this had a disastrous effect on the tenants union, with its internal divisions and with a rival organisation newly created by Cochon. The Union Syndicale des Locataires saw many of its branches collapse or weaken. Half of the 10,000 members had left within a month.

Nevertheless, the constant resort to direct action by the union, inspired by the anarchists and above all by Constant, and the attacks on the sanctity of property were refreshing and in contrast to the uselessness of parliamentarism and the routinism of the socialists.

At the beginning of the First World War Cochon was called up and went through the battle of the Marne. In January 1915, he was detached from military duties to work at the Renault factory at Billancourt.

Sent back to his barracks, he deserted on the 16th February 1917. Arrested in August, he was sentenced by court martial to 3 years public work. During the war he managed to publish a paper, Le Raffut, at Maintenon during 1917. In 1920 he again brought out Le Raffut which appeared from13th November 1920 to 30th December 1922.

He was still involved in the tenants’ movement in 1925- 26 and as a result of his activities, appeared before a Paris court in April 1926. But Cochon’s actions had estranged him drastically from the anarchist movement and he never undertook any further dramatic actions, preferring to remain in the shadows and eventually disappearing into obscurity.

He retired with his compagne Tounette to Pierres, a small town near Maintenon in the Eure–et-Loire department. He came to Paris in the 1950s to speak about the past for a radio programme, Les Reves Perdus (Lost Dreams). Here he was reunited with old anarchists like Louis Lecoin, May Picqueray, Rirette Maitrejean (co-editor with Victor Serge of l’anarchie) and Charles D’Avray.

He died on 25th April 1959 at Pierres.

His son became active in a tenants’ union in the 1970s.

Bibliographie

Patrick Kamoun, V'la Cochon qui déménage, éd. Ivan Davy, 2000 (Extraits disponibles : [1] et [2])

Liens externes

- Georges Cochon et le Syndicat des locataires sur Increvables Anarchistes.

- Cochon contre Vautour, article publié dans le n°32 de CQFD, mars 2006.